CHARLES LEDRAY: MENS SUITS

FROM THE RESEARCH DEPARTMENT

Head-Image

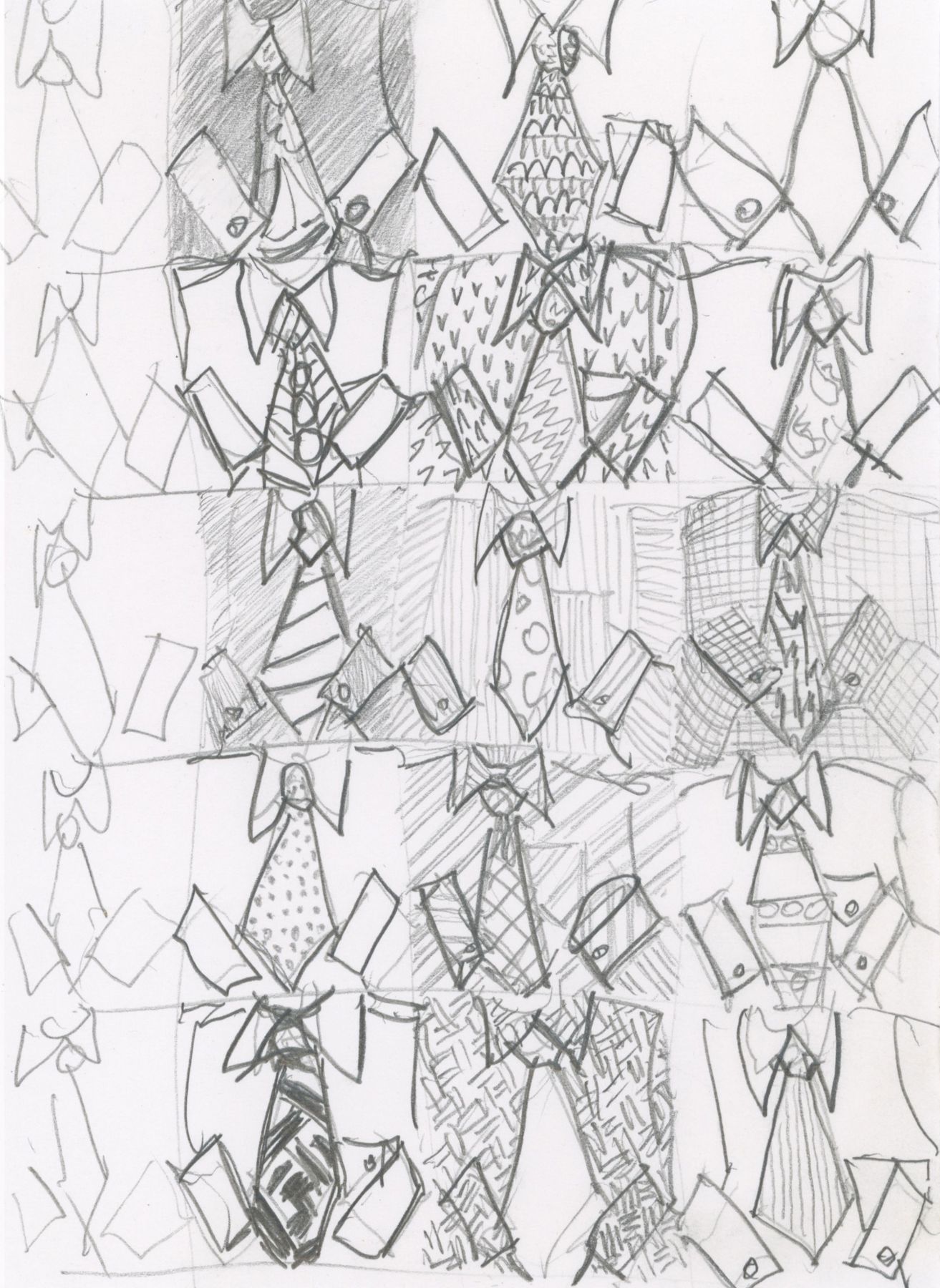

LeDray's studio during the construction of MENS SUITS

This From the Research Department delves into Charles LeDray's most immersive installation, MENS SUITS (2006-2009), commissioned by Artangel and first presented in 2009 in a 19th century Victorian firehouse in London. Subsequent installations were mounted at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam; Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art as part of LeDray’s major mid-career survey that travelled to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and at The Bass Museum of Art in Miami Beach.

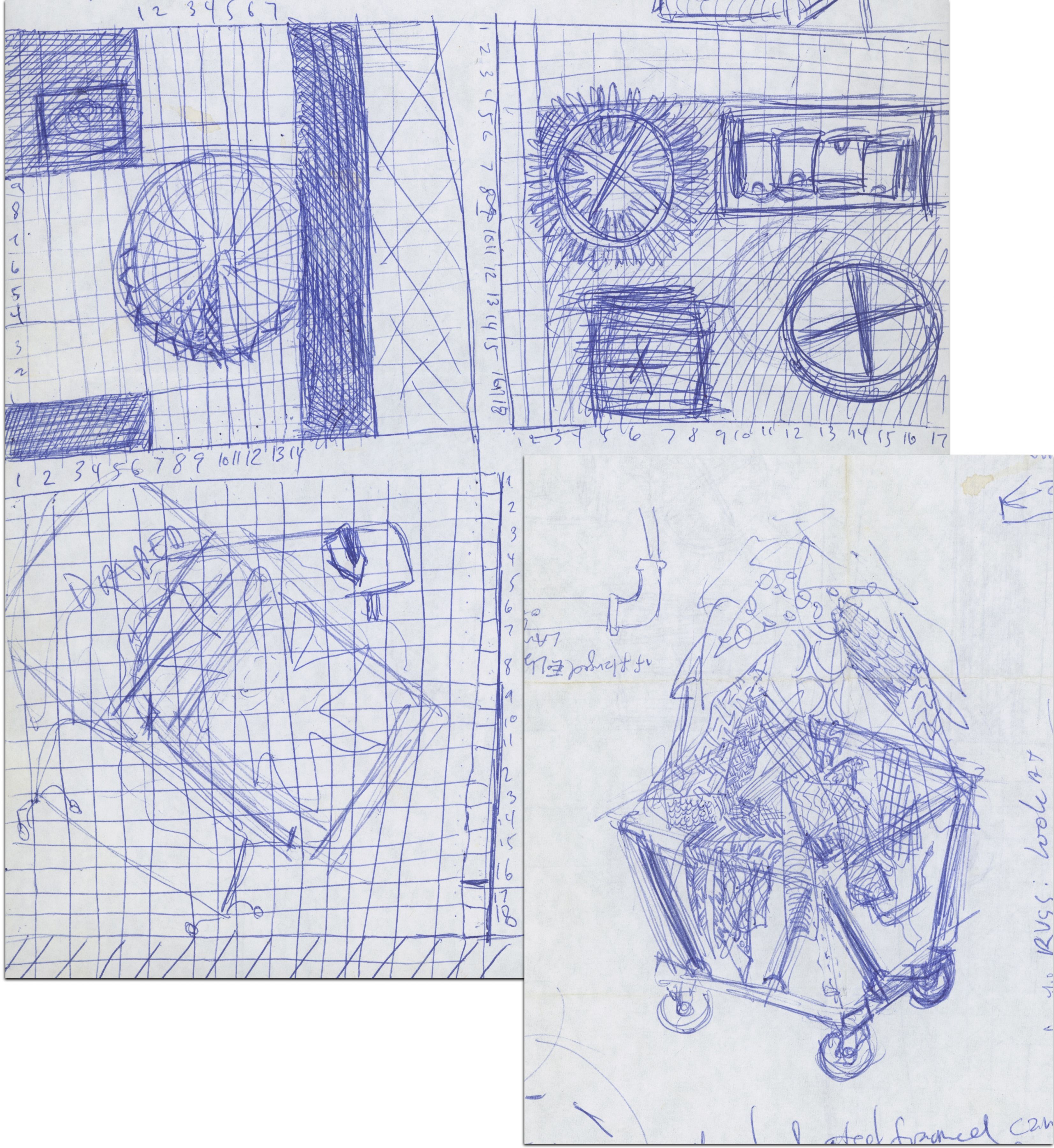

Sketch by Charles LeDray drawn during the creation of MENS SUITS

For more than thirty years, New York-based sculptor Charles LeDray (b. 1960, Seattle) has meticulously sewn, cast, and hand-made a world in miniature. In contrast to the art world’s love of super-sized spectacle, LeDray’s work comprises scaled-down replicas of found or imagined everyday objects whose factual appearance disguises the remarkable means of their creation. He casts these objects (a tie, suspenders, a wedding ring; a stack of industrial bricks, mortar oozing between them; cinder blocks, work gloves, a janitor’s mop) into familiar and enigmatic narratives. The imagery is concrete: eerily detached from reality by scale, yet the artist’s attention to detail renders the work true to life. LeDray’s work conjures up stories of human experience in much the same way that yard sales offer glimpses into other people’s lives.

MENS SUITS comprises three sections of a thrift store selling men’s clothing, each section distinguished by a drop ceiling, lighting fixtures, and worn linoleum tiled flooring. Two of the tableaus represent the store, the third stands in for a back room storage space. Racks and canvas bins are filled with clothes and stuffed with bulging laundry bags. A pinwheel of neck-ties covers a table in one of the showrooms; alongside stands with loosely folded, stained t-shirts and pilling sweaters and racks of crumpled coats with satin linings. Stacks of wooden pallets and an old broom with frayed, gritty bristles fill the back room. Everything, right down to the pipe racks and ubiquitous wire dry cleaners’ hangers with the paper wrapping declaring “We Heart Our Customers,” was handmade, sewn, or cast by the artist. Even the dust coating the suspended ceiling panels adds to the bargain-basement ambiance. These carefully considered details ground the work with a deeply felt sense of reality, as if the viewer is physically present inside a memory of a real time and place.

Michelangelo Pistoletto Venus of the Rags (1967)

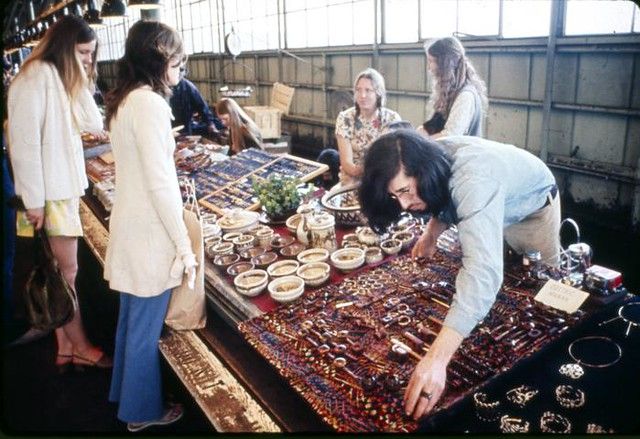

Photo of craft vendors at Pike Place Market, 1970s. Image from the Seattle Municipal Archives

LeDray’s work is rooted in lived experiences. Having grown up in Seattle, he recalls a particularly impactful experience he had with a vendor at Pike Place Market in the 70’s. An older woman selling apparel had set up her station such that a pyramid of clothes was visible behind a curtain, which served the dual function of creating a backdrop and separating the space into designated areas – a sales floor and a storage space. The heaping pile of fabrics calls to mind Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Venus of the Rags (1967) and the image of this scene being tucked away, almost but not quite out of sight, is an idea we see resurface in LeDray’s emphasis on location and vantage point in MENS SUITS.

By itself, the full medium description reads like a laundry list:

fabric, thread, embroidery floss, batting, nylon cord, leather, leatherette vinyl, carpet, wood, wood stain, shellac, polyurethane, paint, glue, nails, metal, metal patina, metal piping, staples, screws, paper, contact paper, cardboard, Eucaboard, Plasticine clay, epoxy resin, epoxy dye, Plexiglas, "Crackle Ice" styrene plastic, compact fluorescent light bulbs, light fixtures, electrical cord, dust

Ledray’s installations are accumulated environments designed to hold your attention. They draw you in with detail, always tempting you to come closer.

In both Robert Therrien’s work and LeDray’s MENS SUITS, scale and detail act in an inverse fashion. When something is blown up, all the details are scaled up and cease to be details. When something is scaled down, it encourages the viewer to lean in and look more closely. In Therrien’s 1994 piece, Under the Table, the surface of the oversized table and chairs seems far less detailed than it would if the same amount of detail were depicted in a piece a tenth of the size.

Robert Gober, Untitled (1989-1996)

Installation view from Robert Gober: The Heart Is Not a Metaphor at MoMA, New York (4 October 2014 - 18 January 2015)

Photography: Jonathan Muzikar

Clothes are strewn everywhere and yet there is not a body to be found, save the headless tailor’s dummy. Alone and spectral, the unoccupied outfit recalls Robert Gober’s handsewn satin wedding gown as it first stood against a backdrop of domesticity and turn-of-the-century ideals of American womanhood at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1989. In MENS SUITS, as in Gober’s Untitled (1989-1996), the body is confronted in new ways and everyday objects are imbued with beauty, mystery, and the psychological intensity of domestic and/or sentimental spaces. The lack of a figure prompts questions like where is the body and whose body is it? It could be the artist - the hidden hand behind the scenes. MENS SUITS alone took three years to make and the viewer is confronted with the hours LeDray spent cutting, sewing, and building each element, challenged to consider the pride of craftsmanship, the drudgery of manual labor, and the connotations of both. The fact that these are used clothes suggests absence, loss, and an individual history tied to each garment. Or the body in question could belong to the viewer – the giant empowered body surveying the scene from above with a god’s eye view. The universe of shrunken goods magnifies the viewer’s ungainly physical presence as well as the privileged position LeDray has put them in. From up above, an overall establishing shot of the scene unfolds and the viewer is able to see things not normally in view. One could argue that the artist is not shrinking the clothes, as much as he is enlarging the viewer by comparison. At the same time, the viewer has the option to change their perspective - to crouch down and see the space from the inside. The contrast of scale between viewer and artwork offers insight into LeDray’s logic: In miniature, close inspection is compulsory. Details are revealed and assessed, demanding a level of engagement that can lead to discovery.

LeDray is particularly interested in the subject of male identity and uses clothing as a stand-in for the archetypical male. There’s the family man, the military man, the businessman, and worker. S.A.M. (1994) consists of gray pants on a hanger with a white dress shirt, tie, and blue blazer draped over top. Stitched onto an outside pocket of the blazer is a round patch declaring the uniform as belonging to a member of “Seattle Art Museum Security” – LeDray once worked at the museum as a guard.

An obvious point of comparison to MENS SUITS is Alexander Calder's miniature Cirque Calder (1926-1931). In pointed contrast to the way in which Calder's circus was displayed at eye level in a 2008 exhibition at the Whitney, is the way in which MENS SUITS sits on the floor when installed, with micro-thin wires supporting the ceiling of each vignette. By situating the work below the eye level of a standing adult, LeDray’s installation forces the viewer to come closer to the work and observe it in its microscopic detail.

“LeDray explores male identity in a funny but deadly serious way. His work asks, ‘Is our clothing a costume that masks ourselves?”

-- ICA Associate Curator Randi Hopkins

Photo taken by Charles LeDray in 1997

The title of the work can be read on multiple levels. It references the type of declarative signage often used in advertising. One store in particular, located in a modern grid-like former bank building in New York’s Flatiron District, whose plain navy signs promised low prices, top designers, and “MENS SUITS”* for the masses. A suit is a type of formalwear typically marketed toward men. Businessmen are sometimes called suits, something can be suited to you, one can follow suit, or a suit could be an appeal to someone who has something you want – like money or a certain lifestyle. LeDray challenges his viewer to question whether the clothes they wear help to define or obscure their true identity. There is also a pugilistic aspect to the title that suggests going against each other, as in the case of a lawsuit. All of this wordplay is active in LeDray’s installation where the clashing patterns themselves battle for a viewer’s attention.

*MENS SUITS was intentionally given in the vernacular, neglecting grammatical conventions.

Postcards from Le Théâtre de la Mode: Homage to René Clair: “I Married a Witch”, original stage set designed in 1945 by Jean Cocteau, and The Théâtre

LeDray’s work is theatrical in a very real sense. By placing a setting with hyper-realistic ‘scenery’ into the gallery space, LeDray draws attention to the theatricality and stage-setting like sense of the gallery or museum. In the same way, his contemporary Karen Kilimnik, blurs the line between stage set and installation in Sleeping Beauty and Friends (2007).

Inspiration for LeDray came in part from a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in 1991 where he saw the Costume Institute’s exhibition of Théâtre de la Mode (Theater of Fashion). The original touring exhibition comprised dozens of one-third-life-size mannequins in miniature French haute couture, promoting a fashion industry struggling to recover in the wake of World War II. Artists and theatrical designers like Jean Cocteau and Christian Bérard were hired to produce the elaborate sets that accompanied the mannequins on their tour across Europe and the United States. The historian Lorraine McConaghy commented on the level of detail in the clothing, saying: “The meticulous attention to detail is so striking ... The buttons really button. The zippers really zip. The handbags have little stuff – little wallets, little compacts – inside them.” By the time LeDray saw the revival in New York, the mannequins had been extensively restored and the original sets had been lost and recreated. Still, the effect was one of awe and revelation and the impact can be seen throughout his work, most notably in MENS SUITS where his painstaking attention to detail and materials is married with a sense of space, collective memory, and theater.

“At a time when contemporary art is often wholly dependent on words, the silent, apparently simple but persistently elusive work of LeDray is akin to a blessing.”

-- Alan Artner

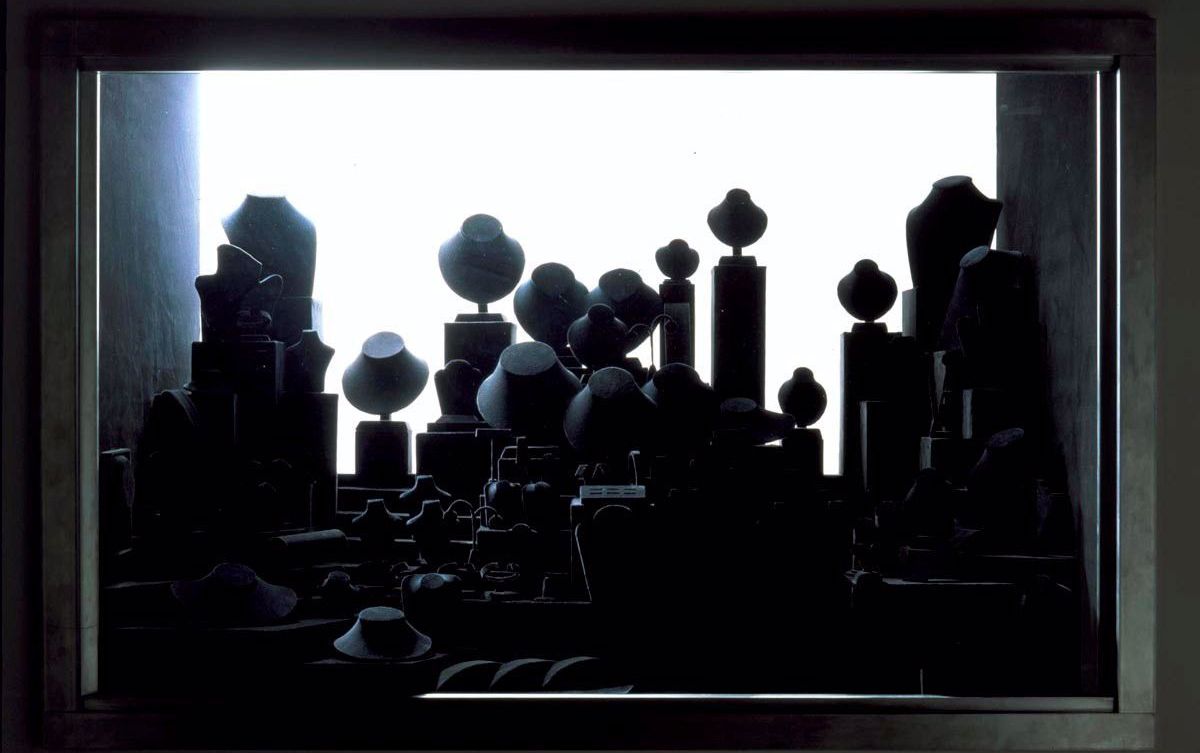

Within his own oeuvre, MENS SUITS most closely corresponds to Jewelry Window (2002), another version of a shop display. What differentiates the window from MENS SUITS is that it is full-scale. Absent any jewels, the backlit black velvet forms become a nocturnal and elegiac landscape. Another setting – another store – with three sub-locations: outside the window where the viewer stands, inside the display, and in the implied interior beyond the frosted glass. The viewer once again has to crane their neck in order to make out the details, in this case cupping their hands to the glass and peering in, and the overall atmosphere of both pieces is that of an abandoned stage set. The individual vignettes in MENS SUITS are simultaneously accessible due to their lack of walls and inaccessible due to their scale and the inclusion of the dropped ceilings. The low lighting and hushed acoustics further inform our understanding of these spaces being vacated, as well as both real and somehow remembered or imagined.

LeDray’s Jewelry Window shares with MENS SUITS a distinct sense of suspended time and space. The jewelry display is empty and only lit from behind, suggesting that the store is closed - either overnight or for good.

Jewelry Window (2002) is on extended view in Metaphor into Form: Art in the Era of the Pilchuck Glass School at the Tacoma Art Museum in Washington.

MENS SUITS depicts a lived experience, resonating with an accumulation of memories. In a similar fashion, The Jesus Corner (1982/83) by Edward & Nancy Reddin Kienholz depicts the sort of place which might trigger memories and feelings on a deeply personal level.

There is something anti-monumental and disconcerting about MENS SUITS. The store is open but nobody is there, creating an empty landscape of people’s cast-offs, stage lit by fluorescent tubes. LeDray’s work communicates a certain type of homesickness – memories of another time and place. These are real places. Real clothes. Real people. By directing our attention to the details of his everyman’s discarded clothing, LeDray points out the way in which we indulge in nostalgic self-reflection by projecting our feelings onto inanimate objects. His work may evoke a sense of mourning for the lives implied by absent bodies. This habit of tugging at the viewer’s memory and heartstrings is in keeping with Robert Gober and Mike Kelley, contemporaries of LeDray who share a similar interest in themes like social and economic class, as well as an integrity in terms of production quality and attention to fine detail.

LeDray originally installed Workworkworkworkwork (1991) on the sidewalk of Manhattan’s Astor Place, transforming the pavement into a pedestal. Many of LeDray’s central concerns are introduced here: the juxtaposition of high and low, repetition and variation of forms, and the use of miniatures to magnify detail.

The lived-in look and seemingly haphazard arrangement of handcrafted suits in MENS SUITS recalls LeDray’s first major installation, workworkworkworkwork (1991), comprised of 588 tiny handmade objects (including clothes, shoes, books, magazines, sofa cushions, bedding, etc.) that he originally displayed in 23 groupings right on the sidewalk, alongside life-size street sales held by homeless and low-income people. In this context, the miniaturization reads as a reflection of the small social status attributed to these marginalized people who have been reduced to selling what others have discarded. The work speaks to conditions of poverty and desperation, as well as wealth and privilege. Richard Dorment best summarized this aspect of LeDray’s intention when he said the following in his review of the Artangel installation:

“For me the most helpful context in which to view him is as the heir to American realist artists of the Depression era. Though he never represents the human figure, the world he shows us is the city life that Reginald Marsh would have recognised. He looks with infinite compassion on the belongings of the dispossessed and the down and out, the downside of the American dream.”

"Though he never represents the human figure, the world he shows us is the city life that Reginald Marsh would have recognised."

-- Richard Dorment

Political, pop cultural and art historical references can be found throughout LeDray’s works. The Alsen Twins (2015-2017) consists of two bags of Alsen Portland cement powder poised on concrete blocks. The composition is a formal nod to Jasper Johns Painted Bronze (Ale Cans) (1960, Museum Ludwig, Cologne) while the materials themselves pay tribute to the late great Alsen Portland Cement Company of upstate New York. The punny title and leather belt cinched tightly around one of the bags serve as playful references to the entrepreneurial Olsen Twins and their fashion empire.

Other references to earlier important and influential American artists include, A Course of Empire Bricks (2015-2017), which refers to a Carl Andre stack of actual Empire bricks on permanent display at the Judd Home and Foundation in Soho. Where Andre’s Manifest Destiny (1986) is stark and meticulous, LeDray has applied a thick layer of mortar, which he allows to seep messily out from between bricks. The block of salvaged wood the tower stands on is decaying. Altogether, the work is in the process of becoming and decomposing simultaneously. The title speaks to Thomas Cole’s The Course of Empire (1836) showing the rise and fall of a civilization. The Empire bricks themselves reference bygone east coast industries. Despite being one of the defining industries in the history of the Hudson River, the rise of cement, cheaper European imports, The Great Depression, and World War II caused many brickyards to shut down. Very few tangible traces remain of facilities like The Empire Brick Company, where the literal building blocks of our society were made.

Sketch by Charles LeDray drawn during the creation of MENS SUITS

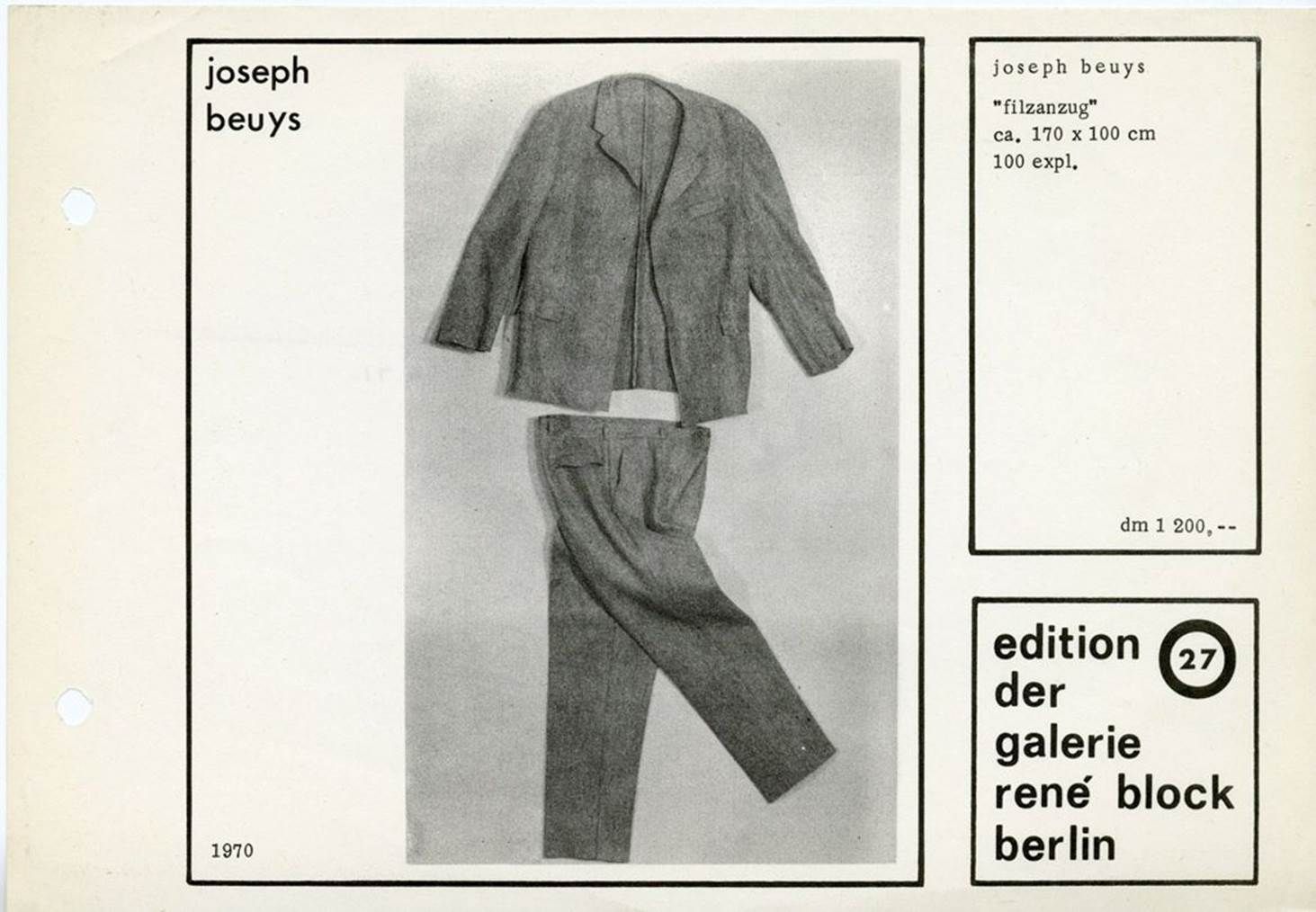

Felt Suit (Filzanzug), 1970 is a two-piece suit made from coarse grey felt from an edition of one hundred identical outfits, all produced in the same year by the German artist Joseph Beuys. Arguably his most famous multiple, this simple ensemble was modeled after one of Beuys's own suits, with the arms and legs lengthened. It has its origins in the performance event 'Action the Dead Mouse / Isolation Unit' of 1970 where Beuys, in collaboration with American artist Terry Fox, protested the Vietnam War at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. Beuys believed that art should be a vehicle for social change and began producing works in multiples in the 1960s in an effort to combat the elitism of the art world. This work represents an extension of the sculptures Beuys made with what he called his ‘survival materials’ – felt and lard, primarily – which he used to convey protection and warmth as both a physical state and spiritual idea. The straightforward title further reinforces the importance for Beuys of practical function over decoration. Where LeDray’s Lilliputian garments are each distinct and highly detailed, with functioning zippers and implied individual histories, Beuys’s suits are elongated, purely practical, and stripped of any ornament or individuality.

Installation view from David Hammons’ 1991 exhibition at Jack Tilton Gallery, New York

Inspired both by Duchamp’s ready-mades and by Arte Povera, Hammons used abandoned materials found in the street to create art objects and installations that speak to issues of race, class, experiences of otherness. The head of the “Central Park West” sign rests on the ground, there is a portable music player balanced on the bike seat, and a dark jacket hangs from the handlebars. He has positioned transportable objects so that they are stuck, creating an environment that emphasizes of the immobilization of movement. Hammons uses the reference to one of Manhattan’s most recognizable neighborhoods as well as the various shades of black clothing to suggest both funerary attire, as well as the unofficial art scene uniform.

William N. Copley’s Bonjour Monsieur Magritte, 1977, courtesy William N. Copley Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Known by his signature name CPLY (pronounced ‘see-ply’), William N. Copley was a major figure of post-war painting primarily known for his eccentric and untrained style based on the traditions of Dada and Surrealism as well as American Pop Art. His installation, Bonjour Monsieur Magritte (1977), consists of black coats, bowler hats, and umbrellas neatly lined up inside a closet that was originally installed in artist's Manhattan apartment from 1977–1980 and later moved to his Roxbury residence in Connecticut. In addition to being an artist, Copley was a longtime friend and gallerist to René Magritte and this piece is a cheeky nod to the uniform and motif for which the Belgian Surrealist was best known. For Magritte, the bowler-hatted gents that populated his works were used as stand-ins for the bourgeois everyman. As Magritte said in 1966, “The man with the bowler is just a middle-class man in his anonymity. And I wear it. I am not eager to singularize myself.” As bowler hats fell out of fashion, the symbol Magritte had chosen to represent anonymity ironically became his iconographic signature, so much so that Copley imagined the closet the artist selected his clothes from every morning to consist of nothing but bowlers, suits, and umbrellas.

Copley’s installation is self-reflexive, it is art about art while Hammons and LeDray are making art about life. All three works use clothing to suggest a figure: LeDray has created custom “found” objects – handmade ready-mades – that evoke real people and real memories, there is something haunting about Hammons’s empty black suits that speaks to the missing bodies they represent, and Copley’s closet functions almost as a portrait of Magritte.

LeDray often employs concepts of seriality, repetition, and variation of form to engage with notions of craft and the handmade. Using the idea and history of miniatures to reveal and revel in labor, he concretizes each object’s existence. In MENS SUITS each element is completely unique, astonishingly detailed, oddly particular, and convincingly lived-in. In the context of a secondhand store, the sheer abundance of clothing sharpens our awareness of the expendability of taste and of things, as well as the value of skill and craft in our production oriented consumerist society.

In 1991 LeDray saw David Hammons installation of Central Park West and Death Fashions (both 1990) in his debut show at Jack Tilton Gallery, New York. Installed together, the various elements consisted of a coatrack filled with jet black dresses, pants, shirts and jackets, as well as a found “Central Park West” street sign speared through a bicycle with a flat front tire. With MENS SUITS as with Central Park West and Death Fashions there is an informality to the arrangements and repetition of elements within their installations. What unifies these works is their engagement with seriality, as well as the broader comments being made about identity and clothing. While LeDray’s work questions the very nature of the art object through its serial reproduction, Hammons uses repetition of structures to create a sense of ritual and sameness.

Detail photo from installation of MENS SUITS

The god's eye view which the viewer occupies in MENS SUITS brings to mind Chris Burden's installation of slightly-larger-than-life uniforms in L.A.P.D. Uniforms (1993), which towered over the viewer, shrinking his body in contrast.

“Beyond the immediate pleasures offered by the kaleidoscopic array of patterned and coloured materials and the astonishing degree of detail, LeDray’s carefully constructed world offers a meditation on appearance and identity, sameness and difference; a mise-en-scène of our current social and economic condition and the way it uses and values people and things; and a reflection on the intertwining of sculpture and the vernacular over the past century.”

-- James Lingwood in Longing to Belong

Ledray’s installations are accumulated environments designed to hold your attention. They draw you in with detail, always tempting you to come closer, look longer. Through his use of clothing he underscores how what we wear is inextricably interwoven with identity. It is this humanity, present across LeDray’s distinctive body of work that imbues each piece with its subtle magnetism.

In myriad materials such as sewn cloth, ceramics, carved human bone, LeDray’s works are marked by artistic invention, masterful handling of technique, and an uncanny manipulation of scale. Charles LeDray's major installation MENS SUITS (2006-2009) was included in Corpus Domini. Dal corpo glorioso alle rovine dell'anima, curated by Francesca Alfano Miglietti at Palazzo Reale, Milan, Italy (27 October 2021 – 30 January 2022).

– Lena Walker

For all inquiries, please write to info@peterfreemaninc.com or call +1 212 966 5154. Peter Freeman, Inc., is open Tuesday to Friday, 10am to 6pm.